Pessimism seems to have reached a peak for AMD after the NVIDIA–Intel deal.

Is this the end of AMD?

Introduction

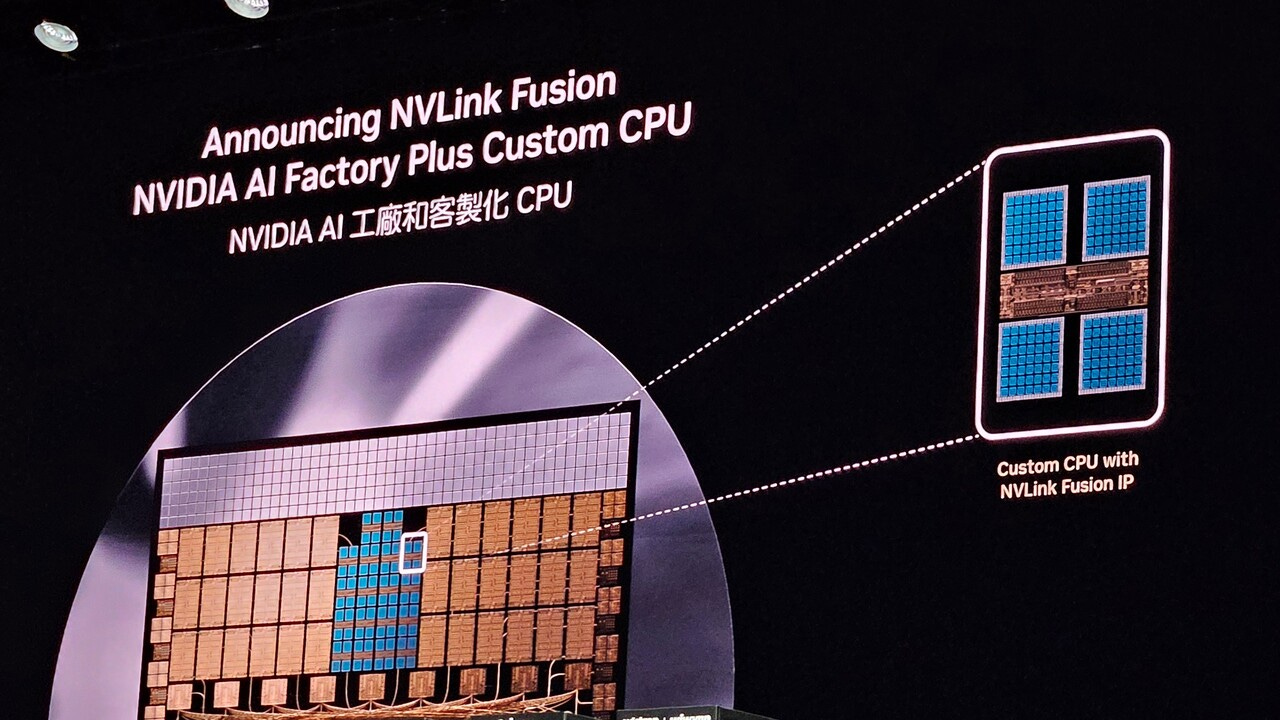

NVIDIA and Intel announced a strategic collaboration that stunned the semiconductor industry. Under this agreement, Intel will design and manufacture custom x86 processors for NVIDIA, targeting both AI data centers and consumer PCs.

Specifically, Intel will create specialized data center CPUs to integrate into NVIDIA’s AI infrastructure platforms, as well as client PC system-on-chips (SoCs) that combine NVIDIA RTX GPU chiplets with Intel’s x86 CPU cores.

In essence, future products will tightly couple Intel’s CPU technology with NVIDIA’s GPU technology using high-speed NVLink interconnects, which comes after NVIDIA announced NVLINK fusion, a new networking technology that enables hyperscalers and businesses to build custom hybrid AI infrastructures by integrating their own specialized processors (ASICs and CPUs) with NVIDIA's high-performance NVLink and rack-scale architecture.

NVIDIA is reinforcing this partnership with a $5 billion equity investment in Intel, giving it roughly a 5% stake.

The partnership is planned to span multiple generations of products, signaling a long-term roadmap rather than a one-off project.

AMD’s Position

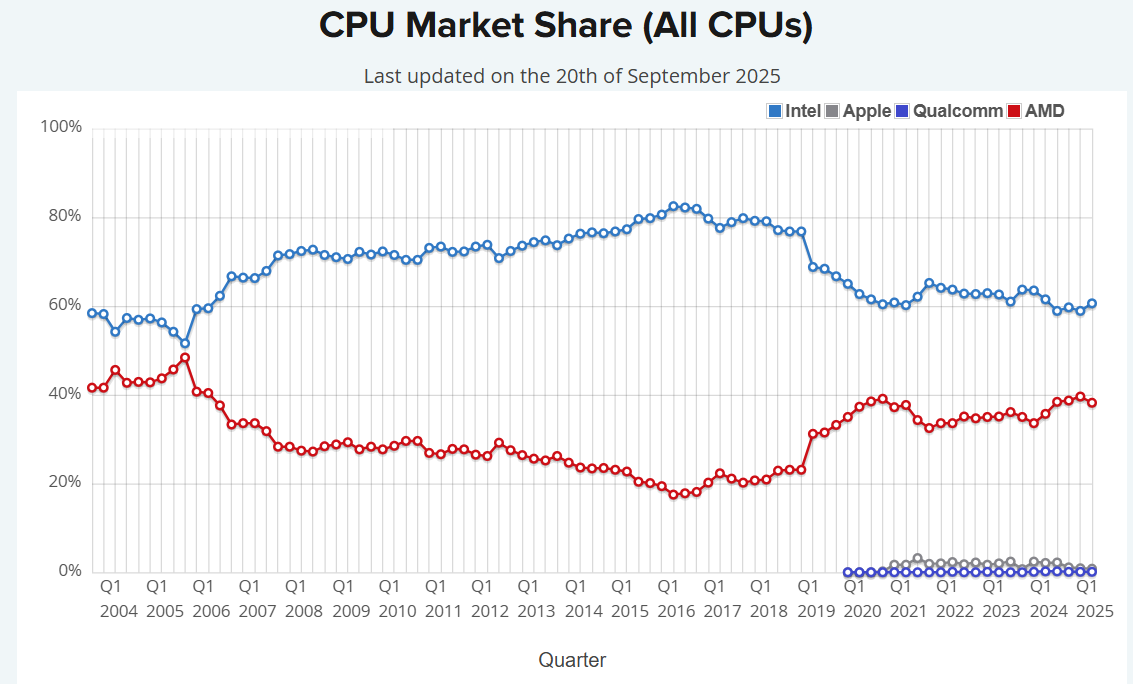

As the industry entered 2025, AMD was on an upswing across several markets. In CPUs, AMD’s Zen architecture steadily eroded Intel’s dominance in both consumer and server segments, gaining market share with strong price-performance and innovations such as chiplet designs and 3D-stacked cache.

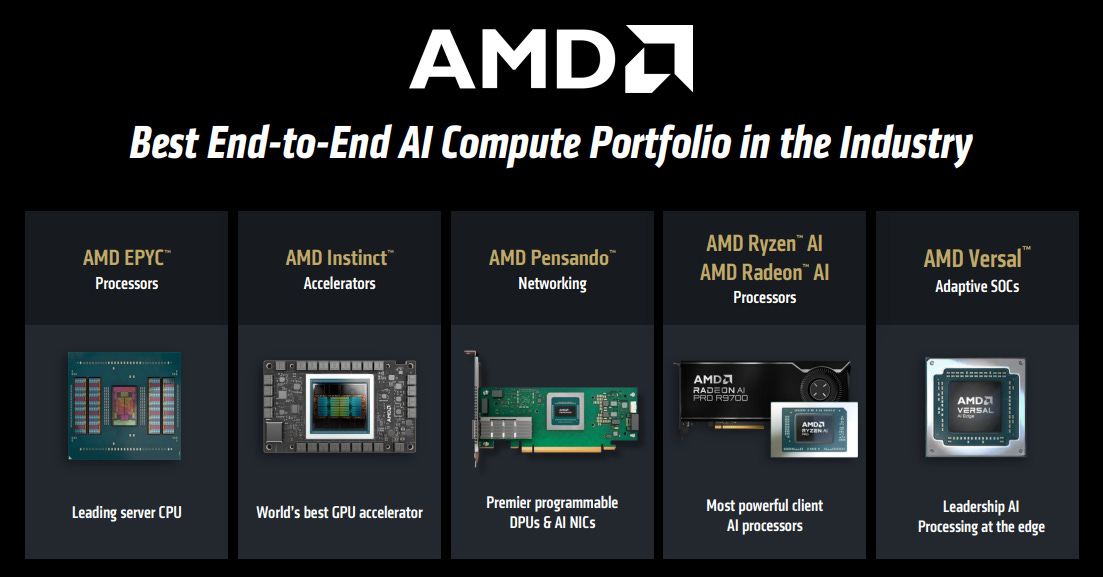

In graphics and AI, AMD’s Radeon GPUs and Instinct accelerators, while far behind NVIDIA in share, positioned themselves as value-oriented alternatives and secured wins in gaming consoles and a few data center deployments.

Crucially, AMD remained one of two guardians of the x86 ecosystem (alongside Intel), benefitting as the go-to alternative for customers seeking choice beyond Intel. By offering both x86 CPUs and high-performance GPUs, AMD held a unique holistic portfolio that neither Intel nor NVIDIA alone could match, until now.

The Concerns

The NVIDIA–Intel alliance effectively unites AMD’s two biggest competitors. For the first time, Intel and NVIDIA are coordinating their CPU and GPU roadmaps, creating combined solutions that resemble AMD’s own efforts (such as integrated CPU–GPU packages) but backed by the market power of two industry giants.

This development risks leaving AMD isolated.

Client Computing Impact: PCs, Laptops, and Handhelds

In the consumer PC market, AMD’s Ryzen processors (particularly the APUs that combine a CPU and integrated Radeon GPU) have been popular in recent years for offering strong multi-core performance and superior integrated graphics compared to Intel’s chips.

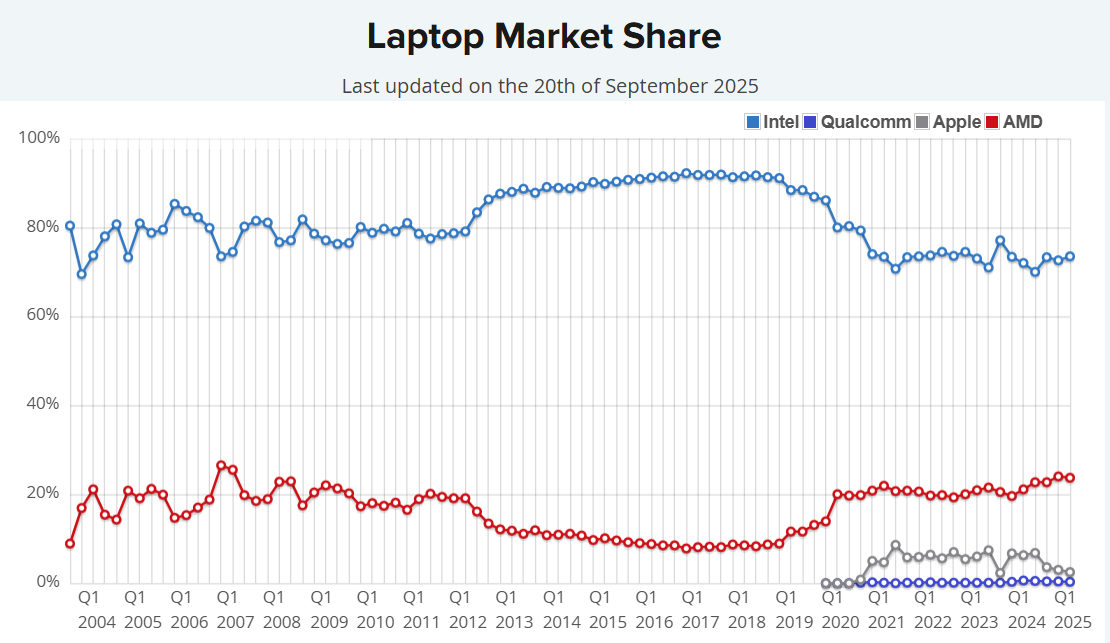

AMD captured roughly 20–25% of the laptop CPU market, helped by its integrated Radeon GPUs winning designs in ultrathins and gaming laptops.

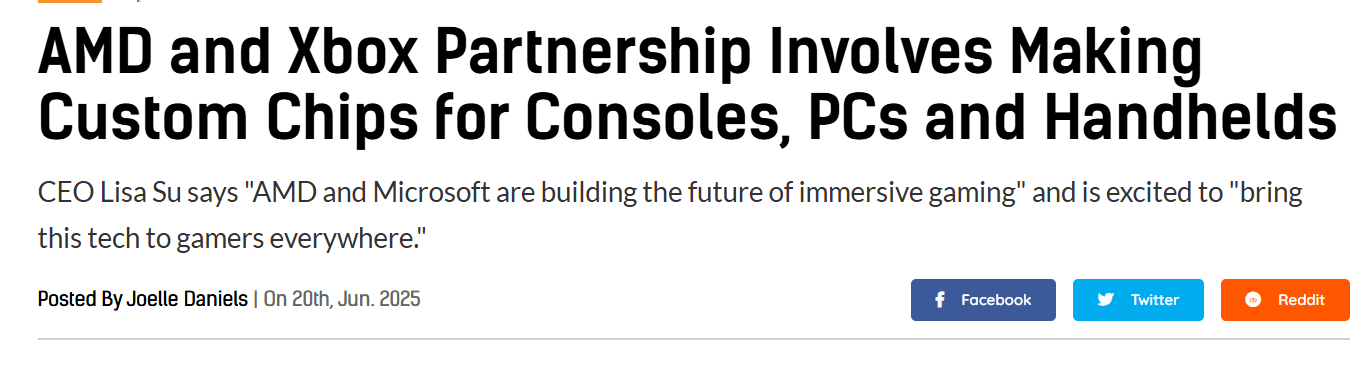

Its APUs have also gained traction in handheld devices like Valve’s Steam Deck and ASUS ROG Ally. Beyond PCs and handhelds, AMD expanded its partnership with Microsoft to design custom chips for consoles, PCs, handhelds, and Xbox Cloud.

The new Intel x86 + RTX SoCs will integrate an Intel CPU with an NVIDIA RTX GPU chiplet on the same package, effectively a direct challenge to AMD’s APUs.

If OEMs gain access to a high-performance, power-efficient NVIDIA GPU on an x86 chip, they may choose to design future handheld consoles or VR devices around that instead of AMD.

Intel still ships about 79% of the world’s laptop processors, while NVIDIA provides 92% of discrete GPUs for gaming.

For consumers, the appeal of an Intel–NVIDIA SoC is clear. Laptop and mini-PC designs could combine Intel’s CPU horsepower with NVIDIA’s graphics performance in a power-efficient, tightly integrated form.

This directly targets the markets where AMD’s APUs have thrived. Thin-and-light gaming laptops and handhelds would benefit from the power savings and smaller footprint of a single-package solution that improves NVIDIA and Intel's current offerings.

Server and Data Center Impact

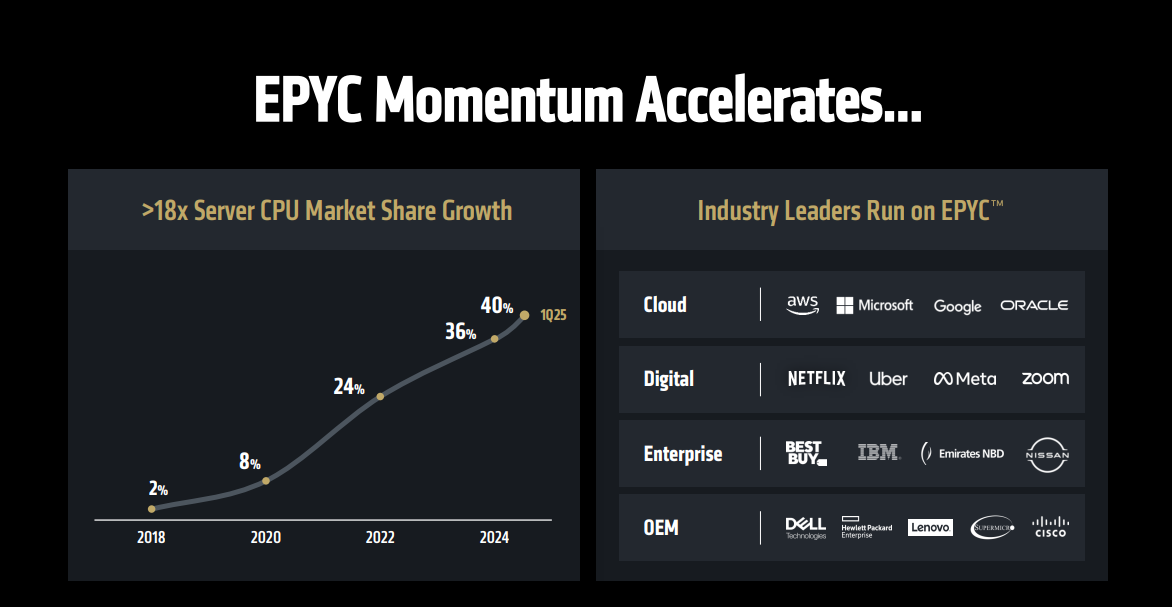

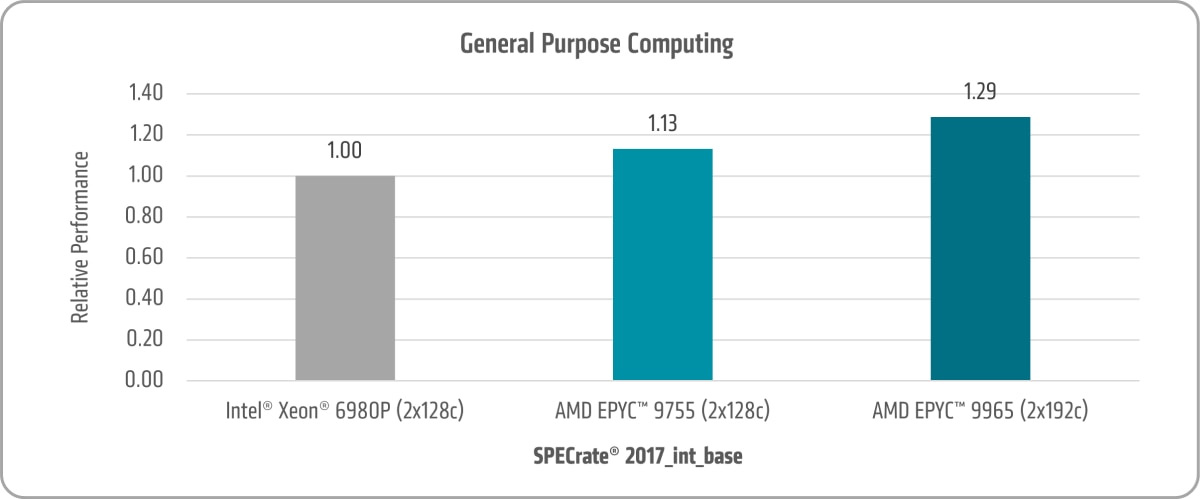

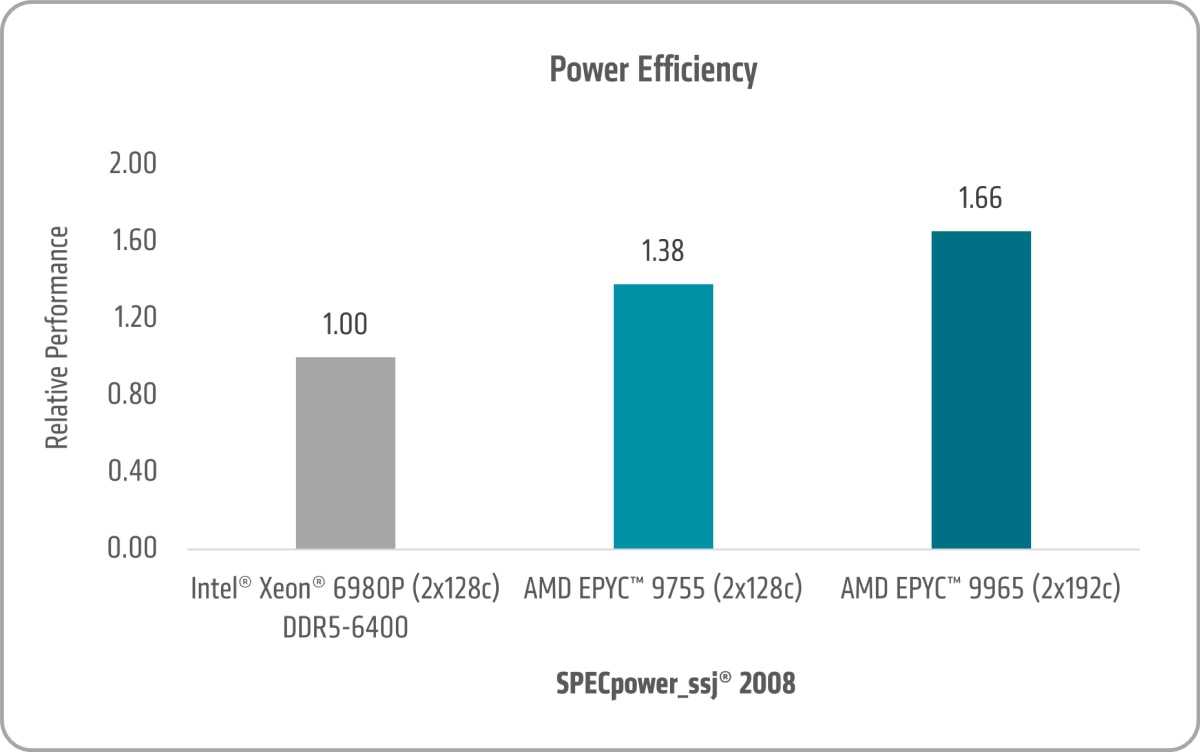

Over the last several years, AMD’s EPYC processors steadily eroded Intel’s dominance in the CPU market. AMD now holds more than 40% of server CPU share, driven by EPYC’s core density and efficiency advantages, particularly in cloud and hyperscale deployments.

The NVIDIA–Intel deal challenges both pillars of AMD’s data center strategy.

For general-purpose server CPUs, Intel gains a lifeline against AMD: tighter CPU–GPU integration for AI and the backing of NVIDIA’s ecosystem.

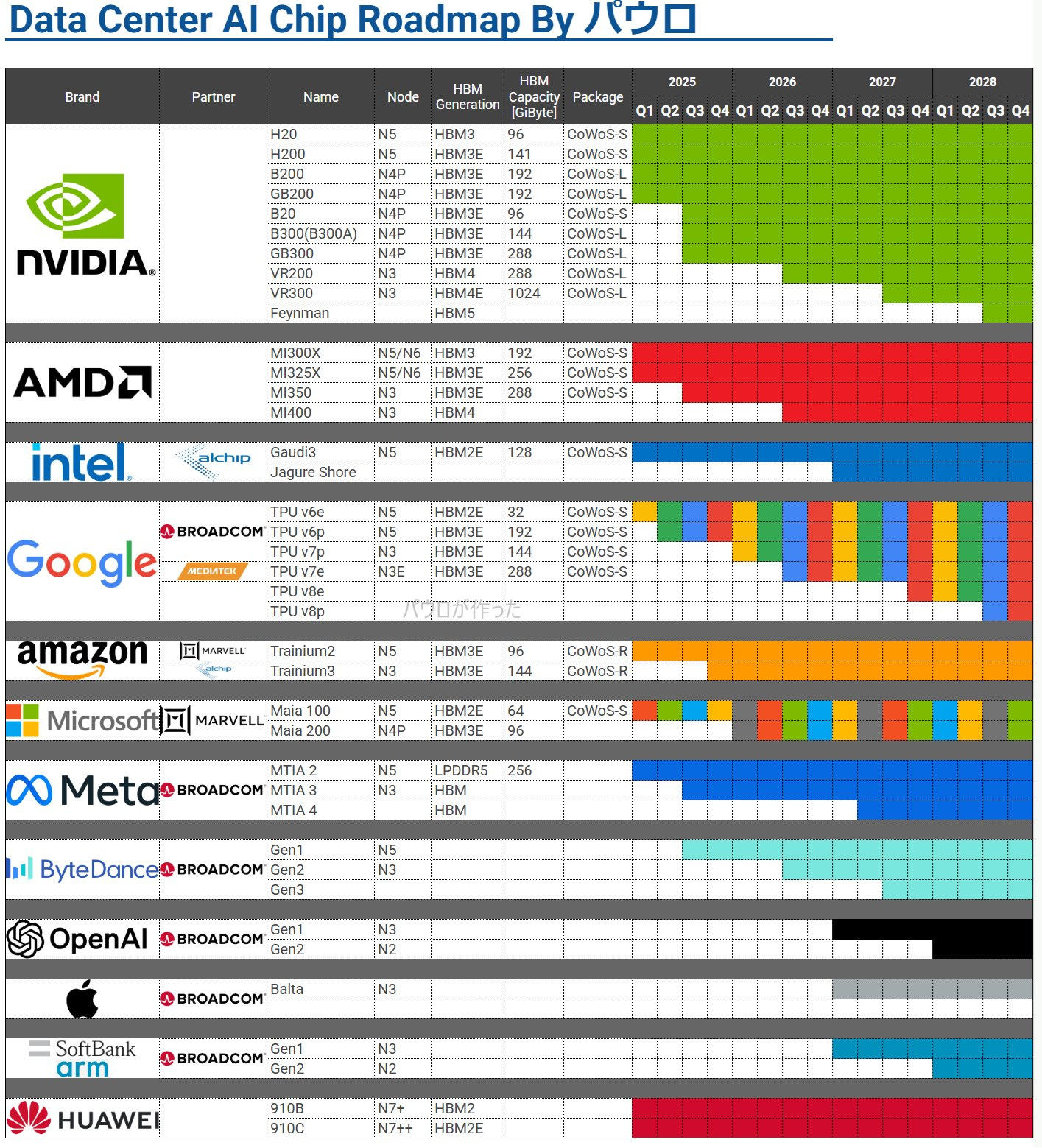

Intel will develop NVIDIA-customized Xeon processors, designed to pair with NVIDIA accelerators in AI servers. NVIDIA plans to use these custom x86 chips in its own AI systems (such as future DGX and HGX platforms) and distribute them to cloud providers.

This makes it likely that NVIDIA’s AI platforms, which once could have used either Intel or AMD CPUs, like the current B200 and B300, will now rely exclusively on Intel, shutting AMD out of valuable designs.

For many customers, the decisive factor is NVIDIA’s software ecosystem (CUDA and its AI libraries). By adding x86 compatibility through Intel, NVIDIA eliminates one of the few advantages AMD’s Instinct series held.

That said, AMD still retains an important advantage: control of both CPU and GPU IP under one roof. This gives it the ability to pursue tightly integrated products on its own timeline.

AMD’s chiplet expertise, pioneered with Ryzen and EPYC, is another competitive strength. While Intel has shifted to chiplet designs and NVIDIA is now embracing chiplets by contributing GPU tiles for Intel’s packages, AMD has years of proven experience in efficiently integrating many dies and heterogeneous IP. Its Infinity Fabric interconnect and advanced packaging technologies have already produced real product benefits, like 3D V-Cache boosting Ryzen gaming performance.

If AMD can innovate faster on chiplet-based designs than a large, slower-moving partnership, its products could stay compelling. For example, next-generation RDNA 5 GPUs are rumored to adopt multi-chiplet designs, which could leapfrog NVIDIA if it remains on monolithic dies longer.

Similarly, AMD could integrate AI accelerators from Xilinx FPGA and AI Engine IP directly into future CPUs and APUs, creating unique advantages such as adaptable AI inference at the CPU level.

Another key battleground is the software ecosystem. NVIDIA CUDA dominates GPU computing and AI development.

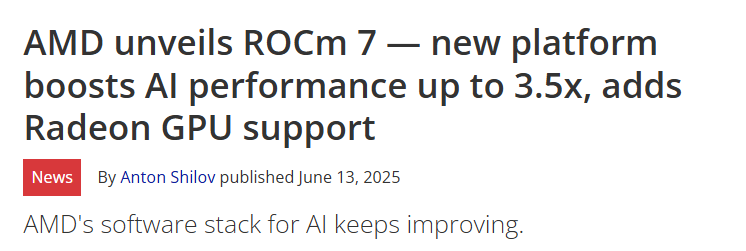

Intel is advancing oneAPI for cross-architecture support, which will be optimized for its collaboration with NVIDIA. AMD, meanwhile, has promoted ROCm as an open alternative.

So far, CUDA’s lock-in has been a major barrier for AMD. The Intel–NVIDIA partnership may tighten that grip, as CUDA gains more seamless reach into x86 systems. This would make it even harder for AMD to persuade developers to optimize for Radeon and Instinct GPUs.

To compete, AMD will need to highlight that it is the open choice in the industry. ROCm 7 is a step towards that, but more collaborative efforts with the developer community will be needed.

Their co-developed networking architecture to disrupt NVLink , UALink, is built to give data centers a flexible way to connect large numbers of chips without being tied to NVIDIA’s system.

If data center operators become wary of relying too heavily on NVIDIA, now closely tied to Intel, they may view AMD’s open ecosystem as a more attractive alternative.

However, as much flexibility as AMD offers, the choice of platform for large-scale deployments will come down to total cost of ownership and performance, which remain the decisive factors.

Reality Check

Designs Take Time

Designing custom x86 processors for NVIDIA’s platforms (both data center and PC SoCs) is a multi-year process, not something achieved in a few quarters. OEM qualification cycles, software and firmware development, and supply chain build-outs mean late 2027 and beyond for any meaningful volume. This gives AMD time to continue executing on Zen, Instinct, APUs, packaging, and ROCm.

In the near term, NVIDIA rack-scale NVL systems (GB/Rubin) are Arm-based Processors+ GPU. The custom Intel alternatives will complement that, but they will not replace it overnight, and certainly not soon.

At the same time, HGX and PCIe accelerator boards, where the host CPU is x86, remain a massive market in which EPYC continues to compete directly. Until NVIDIA doesn’t closely integrate co-developed x86 CPUs, AMD will still have market share available in EPYC + NVIDIA Accelerator setups.

AMD Still Leads in Various Fronts

EPYC Turin delivers superior core density and performance per watt, driving lower TCO for virtualization, databases, and scale-out compute.

These advantages are what powered AMD’s market share gains, and they do not vanish simply because a future Intel–NVIDIA product has been announced.

AMD Advantages:

Chiplets and packaging: AMD’s chiplet strategy with Ryzen and EPYC, plus innovations like 3D V-Cache, are already proven at scale. AMD can iterate faster on multi-die architectures, while Intel and NVIDIA coordinate their first co-designed x86 + RTX SoCs.

APUs and client leadership: AMD already ships high-performance APUs across laptops and handhelds. Intel and NVIDIA must still prove that their one-package solution can meet power efficiency, thermal, and cost requirements in those constrained form factors.

Process cadence: Zen 6 is expected to reach leading-edge nodes early. AMD has a credible path to 2 nm-class CPUs ahead of broad Intel 18A desktop ramp-up, which sustains their likely technological edge for the future generation, too.

Open interconnect and ecosystem: With ROCm maturing and open interconnect initiatives like UALink gaining partners, AMD can position itself as the less locked-in alternative to NVLink-centric stacks. This appeals to data center buyers concerned about dependence on a single vendor.

Conclusion

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Daniel Romero to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.